Author: Sean Krivitsky, Class of 2026

Many organisms, like fish and insects, are capable of living in extreme conditions far outside of the viable range for humans. While some bacteria can live in hot geysers, others live in the extreme cold, relying on adaptations such as the expression of antifreeze proteins (AFP) to survive. These proteins help adapt to the cold by depressing the freezing point of a solution. However, when cells eventually do reach their freezing point, it can be quite damaging. To prevent this, some AFPs can promote the nucleation of ice crystals, helping to ensure a more controlled formation of ice crystals within the body. This function is carried out by the proteins’ ice binding surface domain. Recently, researchers at the City University of Hong Kong sought to better understand the ice nucleation capacity of an insect AFP at an atomic level to better understand this process.

Led by Yue Zhang, the team of scientists studied the insects by taking advantage of an advanced technology called molecular dynamics (MD), which involves simulating the motions of biological processes on a short time scale by continuously solving classical physics problems. This allows the dynamics of short-lived events to be better understood. While these calculations are incredibly computationally expensive, this group chose to represent all atoms in the simulation. This means that functional groups on the protein were not condensed to be represented as a single point, and all water molecules in the simulation were shown explicitly to help to more accurately model hydrogen bonding.

This short timescale molecular simulation revealed that AFPs use a specific region called the ice binding surface (IBS) in a 3-step pathway. After promoting the first attachment of water molecules to the cell surface to anchor it, the ice binding surface encourages the formation of a thin structure of ice on the IBS surface. Specifically, a groove on the IBS formed by hydrophobic functional groups allows for this initial confinement and anchoring of water molecules for ice formation. This seed is later used by the IBS to nucleate 3D ice formation, stacking consecutive sheets of ice to form 3D ice crystals.

Overall, by demonstrating that specific amino acids in the polypeptide chain align to make this phenomenon possible, Dr. Zeng and colleagues uncovered the mechanism by which a subclass of AFPs can facilitate ice freezing. This is also the first use of an all-atom simulation to represent such a process, demonstrating its application to subsequent studies on other complex biological processes related to ice nucleation.

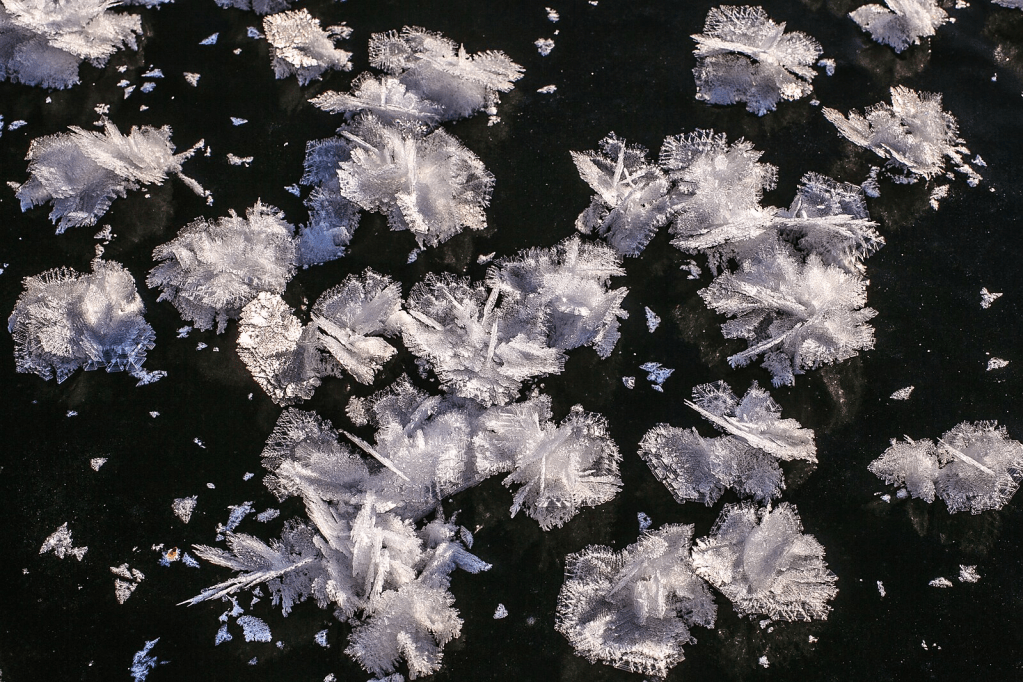

Figure 1: Image of a collection of snowflakes

Works Cited:

[1] Zhang, Y., Wei, N., Li, L., Liu, Y., Huang, C., Li, Z., Huang, Y., Zhang, D., Francisco, J. S., Zhao, J., Wang, C., & Zeng, X. C. (2025). Fully atomistic molecular dynamics simulation of ice nucleation near an antifreeze protein. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 147(5), 4411–4418. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c15210

[2] Image retrieved from: