Author: Tiffany Ang, Class of 2025

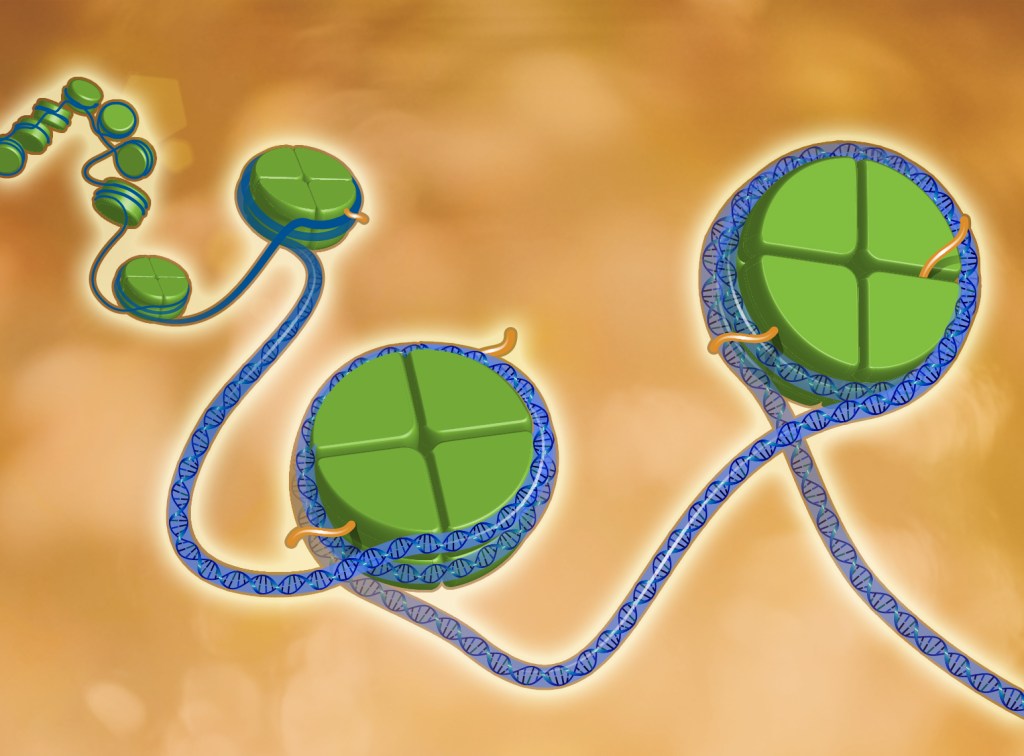

Figure 1: A visualization of epigenetic modifications that shape gene expression without changing the genetic code.

DNA methylation-derived epigenetic clocks are powerful tools for assessing biological aging and age acceleration–the difference between biological and chronological age. Unlike chronological age, which fails to capture the impact of biological and environmental influences, age acceleration explains individual differences in cognitive functions such as processing speed and working memory, both of which decline with age. Processing speed refers to the time needed to respond to information while working memory involves retaining information while performing distracting tasks. Dr. Zavala and colleagues at Stony Brook University hypothesized that greater age acceleration would predict slower processing speed and poorer working memory.

In this study, participants completed cognitive assessments five times over 14 days. Blood samples were collected for DNA methylation analysis to estimate epigenetic age and age acceleration using various epigenetic clocks, including Horvath 1, Horvath 2, Hannum, PhenoAge, and GrimAge. Processing speed was measured using a symbol search task while working memory was assessed with dot memory and N-back tasks. Positive deviations between epigenetic and chronological age indicated age acceleration.

The study found that positive age acceleration was linked to slower processing speed and greater intraindividual variability in cognitive performance. Interestingly, chronological age was associated with less variability. Intraindividual variability, or fluctuations in cognitive performance over time, is an early indicator of cognitive decline. These findings suggest that epigenetic age is a stronger predictor of cognitive outcomes than chronological age and explains variation among individuals of the same chronological age.

Notably, the average age acceleration was close to zero across all clocks, suggesting little overall biological age deviation from chronological age. For example, with the Horvath 1 clock, being one year epigenetically older than one’s chronological age was associated with fewer accurate responses per minute. Higher intraindividual variability was consistently linked to positive age acceleration across all clocks, whereas chronological age was associated with lower variability.

These findings highlight that age acceleration is a stronger predictor of cognitive function in daily life than chronological age. However, age alone cannot account for differences in age-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Future research aims to track longitudinal changes in cognitive function through repeated assessments, examining how age acceleration evolves and its impact on cognitive health.

Works Cited:

[1] Zavala D.V., Dzikowski N., Gopalan S., Harrington K.D., Pasquini G., Mogle J., Reid K., Sliwinski M., Graham-Engeland J.E., Engeland C.G., Bernard K., Veeramah K., Scott S.B. Epigenetic Age Acceleration and Chronological Age: Associations With Cognitive Performance in Daily Life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024 Jan 1;79(1):glad242. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glad242. PMID: 37899644; PMCID: PMC10733172.

[2] Image retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Epigentics_(27058470305).jpg